Native Son

It seemed there was almost nothing this member of the Blackfoot tribe could not do with excellence and verve.

When his identity was revealed, tragedy followed.

Native Son

by Randell Jones

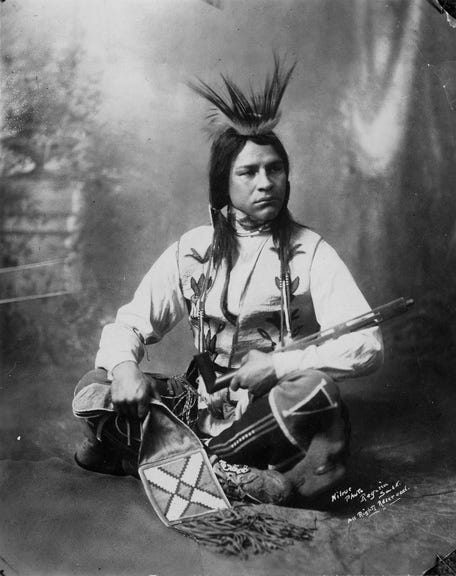

CHIEF BUFFALO CHILD LONG LANCE was one of the most celebrated Americans of the day between World War I and the Great Depression. He was a war hero; his autobiography was an international best seller; he performed in a silent movie. As a journalist, Long Lance was an outspoken advocate for Indian rights. And, during his school days, he outran the great Jim Thorpe repeatedly. It seemed there was almost nothing this member of the Blackfoot tribe could not do with excellence and verve. Nothing, except accomplish all that he did had his full identity been known. And, when it was revealed, tragedy followed.

In 1928, Long Lance wrote a fictional account of growing up as the son of a Blackfoot chief in Montana’s Sweetgrass Hills. Advertised as his “autobiography,” it shared graphic anecdotes of Indian life. He was already an accomplished writer, having worked for a decade as a journalist in Calgary, Canada. He was popular on the speaking circuit and among New York’s social set as well. Because his book was recognized by anthropologists, Long Lance became the first American Indian inducted into New York’s prestigious Explorers’ Club.

Long Lance came to write his “autobiography” because he had earned the trust and respect of the Blackfoot Confederacy years before for his writing about Indian rights and needed reforms in the government’s re-education policies. He had spent much time at the Indian reserves. In appreciation, the Blood tribe gave him a ceremonial name, “Buffalo Child.” This tribal recognition enabled him to claim that he was Blackfoot. Before that, Long Lance had said he was a Cherokee from Oklahoma. Be that as it may, during the 1920s, Long Lance was active in the life of Calgary, a member of the Elks Lodge and coach of the local football team. He was a hardworking, productive member of the community.

Long Lance had come to Calgary, Alberta, in 1919 after he was honorably discharged from the Canadian Expeditionary Force following his service in France where he was twice wounded in 1917 and three times decorated. He had enlisted for active duty in Canada, because the United States was not yet in the war and he wanted to fight.

He had graduated in 1916 from St. John’s Military School in Manlius, New York. He earned the nickname “chief” because he was the only American Indian in the class; he then added “Lance” to his name. He had earned that opportunity at college with his success at the Carlisle Indian School where he graduated in 1912 at the top of his class which included famous athlete Jim Thorpe and a son of Apache warrior Geronimo.

Without the later enhancements to his name, Sylvester Long had applied to the Carlisle Indian School simply to get an education, claiming to be half-Cherokee. He was admitted, in part, because he could speak a little Cherokee, having learned from Cherokee elders while he was working as an Indian in Buffalo Bill Cody’s Wild West Show. He had taken that job in 1904 after leaving home at age 13.

Home for Sylvester Long was our own Winston, North Carolina. His father worked as a janitor in the school system. They lived in a black section of West Winston. His parents’ heritages were Lumbee/Croatan, Cherokee, white, and black; but, in the South in that day, any black made him “colored,” nothing else. He had to leave North Carolina to realize his potential, to escape the limits imposed upon him by society and by the discriminatory laws that constrained his life even as a citizen of that state.

In 1930, Chief Buffalo Child Long Lance appeared in The Silent Enemy, a story about Ojibwe people battling hunger. His performance was widely praised; but, during production another Indian raised suspicions. Once revealed as black, Long Lance fell quickly in social circles. The author of his autobiography’s foreword declared, “We are so ashamed. We entertained a n-----.”

Regarded by some as a con artist, Chief Buffalo Child Long Lance was unable to reconcile his accomplished life with what society would allow. In 1932, he shot himself in the heart in Los Angeles, California.

How many more will despair of living a life at odds between who they are and society’s and the law’s imposed limitations? ●

Randell Jones lives in Winston-Salem. Another story about Sylvester Long appears in Scoundrels, Rogues, and Heroes of the Old North State, which he edited was recorded as an audio book by the NC Library for the Blind and Physically Handicapped for its sight-impaired patrons. They released a braille edition as well.

Randell Jones is the author of In the Footsteps of Daniel Boone (2nd ed., 2024) and other books of American history. Find his books at RandellJones.com . He lives in Winston-Salem.

This story is included in “From Time to Time in North Carolina” (2017) by Randell Jones, a collection of his selected guest columns written for the Winston-Salem Journal during the last 30 years. Find the book at RandellJones.com or on Amazon.com.

Or, you can read them here on Substack.com as we post them … wait for it … from time to time.

Subscribe for free to “From Time to Time in North Carolina.”

Also listen to Roy Thompson’s “Before Liberty” articles from 1975/6 as narrated by Randell Jones under “Before Liberty” also found at Substack.com/@randelljones . Subscribe separately to “Before Liberty.”

A profoundly moving tribute. This piece ends with a question that reads like a prayer. Thank you for this lesson in greatness and the wounds of history.